A New Chapter For The Portuguese Left

On Tuesday the Portuguese left struck a landmark compromise with the center-left Socialist Party that prompted the fall of the conservative PSD-CDS coalition government. The compromise is landmark not for its ambitions, but for representing an unexpected truce with a Socialist Party to achieve the immediate objective of toppling a government that implemented the Troika’s austerity program since 2011.

It’s a difficult compromise for the Portuguese left. Both the Communist Party and Left Bloc campaigned fiercely against the austerity-lite program the Socialist Party ran on in general elections just over a month ago. It’s also a compromise over substantial historical and ideological divisions. These divisions go back to the 1974-1975 revolutionary period during which Portugal’s international alignment, economic model, and state form were fiercely contested in the streets, army barracks, the constituent assembly and in six provisional governments. Through long stretches of the revolution, the Socialists and the center-right were allied on these matters and opposed to the Communist Party and other left-wing forces.

While historical and ideological differences between the Socialist Party and forces to its left still maintain relevance today, the political imperative of toppling the most right-wing government since the revolution motivated the entire parliamentary left to reach an accord to find an alternative government solution. Outgoing prime minister Passos Coelho and his deputy Paulo Portas provoke a revulsion on the Portuguese left comparable to that caused by Thatcher in British left politics. To contrast his government with PASOK in Greece, Passos Coelho sought to win over creditors and investors with the idea of being a willful reformer. The “good student” of austerity was in large part branding for foreign consumption, but at home it nonetheless earned him the designation of being “more troika than the troika.”

It would take a month of negotiations between the Socialist Party and forces to its left to ensure the defeat of Passos Coelho. Going in, the Socialist Party leader Antonio Costa made it clear he would not contribute to a so-called “negative majority”. This meant his party would abstain in parliament and permit the conservatives to form a minority government, absent an alternative government solution. This was a difficult moment for the party, potentially facing its second leadership contest in two years, a sharp contrast to the expectations months earlier of an election victory.

The Left After Elections

The Communist Party and Left Bloc had to navigate a difficult political scenario. They could have understandably identified the Socialist Party as too centrist to work with, or they could have intervened to extract the maximum economic concessions. There were persuasive arguments to be made for either option, which adds to the significance to their ultimate decisions to intervene.

After winning a surprising 10% of the vote in October 4th elections, Left Bloc may have been forgiven for sitting back and watching the Socialist Party bleed support from internal divisions and the stigma of propping up a conservative government, but the benefits to such a strategy aren’t as obvious on closer examination. Left Bloc’s support has been volatile over the past six years. In 2009 it won a breakthrough 10%, making it one of the standout, emerging left parties in Europe. But despite being in opposition to a minority Socialist government carrying out unpopular austerity measures, Left Bloc saw its support nearly halve in 2011 general elections. Its support in opinion polls would again rebound during the height of anti-austerity protests in late 2012, only to then suffer genuinely poor results in 2013 local elections and 2014 European elections.

Left Bloc’s unquestionable asset is their spokeswoman Catarina Martins. During the elections she carried the party from an expected mediocre performance to its best result ever in seats and percentage of votes. By inserting itself into the government formation process and negotiating economic policy, Left Bloc is putting Catarina Martins and its other promising, charismatic MPs in the position where they can be most effective to maintaining and growing the party’s support. The question is whether this personal protagonism produces the same political moderation that has characterized Syriza and Podemos.

The Communist Party’s place in Portuguese politics is different from that of Left Bloc. It’s a broader party organization with a long history and deep ties to the trade union movement; CGTP, its allied trade union confederation, is the largest in the country. Its working class ties can also be seen in its central committee and the working class professions of its members, including its secretary-general Jerónimo de Sousa. This gives the party a stable base of support that has modestly grown in each of the last four general elections, though distant from its best days in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s when the Communist led coalition United People Alliance won between 15% and 19% of the vote.

The Communist Party’s objectives in its dealings with the Socialist Party aren’t that different from Left Bloc’s. The goal for both is to put a line under the austerity of the last government and neutralize the austerity proposals of the Socialist Party. Left Bloc was more public in negotiations and worked off the preliminary demands for the Socialists to drop their proposed four year pension freeze, labor reform, and debasement of the social security system’s revenue stream. The Socialist Party’s revised program reflects these concessions, but more negotiations undoubtedly lay ahead as the compromise must be turned into budgets and government policy.

The Post-Compromise Horizon

The Communist Party and Left Bloc now find themselves as decisive players in Portuguese politics. The Portuguese right, who consider themselves the winners of October’s elections, are furious at being driven from power by a left alliance virtually no one expected. They have made clear that a Socialist minority government can’t count on their votes in parliament to survive. They are promising a bitter, reactionary opposition that adds to the importance of this moment in Portuguese politics. The so-called “arch of governance” between the center-left and center-right is broken, at least for now.

This notionally will give Left Bloc and the Communist Party great leverage over the Socialists, but this leverage runs into the political limits of the Socialist Party and the country’s European economic integration. While a higher deficit itself is not the objective of the left, they’d prefer a higher rate of spending to a budgetary consolidation done at the expense of pensions, wages and services. Depending on the economic situation in the months and years ahead, this preference may clash with the Socialist Party’s commitment to international agreements, including Europe’s Fiscal Compact.

These differences on structural questions as well as others like NATO and debt restructuring made it difficult for these parties to form a government together. While the Communist Party and Left Bloc will still find themselves voting for policies and measures they find insufficient or disagree with, they can better maintain themselves as independent forces with their own political projects outside the discipline of government. Left Bloc MPs like Jorge Costa and Catarina Martins continue speaking of the importance of debt restructuring for “more profound changes” and you can still find the Communist Party promoting and attending recent mobilizations against NATO military exercises in Portugal. These are causes they haven’t abandoned, but which the Socialists do not share and can’t be forced to share.

Portugal, like the rest of the Euro Zone, will ultimately need a far more ambitious political program than the one found in this compromise. The spectrum of this deal is modest, but it does permit the Communist Party and Left Bloc to frame themselves as defenders of the class interests of pensioners and workers, negotiating a greater share of income for these groups. Apart from meaningful concessions that can be won, the success of this deal for the Portuguese left will depend on whether it proves to be a quicker path to a more ambitious socialist project than by having chosen opposition to another conservative coalition government.

The Permanency of the Left’s Defeat in Greece

After the painful capitulation of Greece’s Syriza led government to the impositions of the country’s European creditors, one point of consolation for Europe’s left has been “now we know who the enemy is.” Such is the darkness of these times that even this minimalist point must be denied any merit. This isn’t 2010 when the Troika first introduced itself as a creditor junta imposing austerity on a rattled and desperate PASOK government in Athens. Since then there’s been full scale bailout programs in Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus, a second program in Greece and a bank bailout program in Spain; all of these opportunities to witness the monstrosity that is the European Project in moments of existential crisis.

After five years of Troika politics how could a party of the left like Syriza put so much faith in negotiations with European creditors? Looking back over previous months and years it’s not difficult to see how much of the blame for austerity was redirected away from the Troika and at the various national governments merely operating within limits of Europe’s austerity regime. In Greece, this took the form of the Syriza narrative that the PASOK and New Democracy governments were ineffective negotiators. Vague language by creditors referencing debt restructuring was herald as a victory, even though the previous governments won similar vague commitments.

In Portugal, much of the left has fixated on the idea that prime minister Passos Coelho went beyond the Troika. Of course, Coelho built up this narrative himself but it was more image than substance; an effort to build positive publicity of a reformed Portugal that took the medicine without making a fuss. But one only has to look to the Troika’s call for additional measures like suppressing wages, curtailing collective bargaining, and pension ‘sustainability’ to see how much further the Troika wanted to go than the Portuguese government. Still, the idea of a prime minister more pro-austerity than the troika was too much for the left to resist, all the while structural explanations for austerity didn’t get the central focus they deserved.

The hope on the left is that after all these years of Austerity Europe, the capitulation of Syriza will finally build a left consensus on rupture with the euro. I think this is greatly mistaken. Much of Syriza’s capitulation has been blamed on yet another villain, again opting for figures to blame instead of structures. ‘It’s Schäuble who’s ruining Europe by trying to drive Greece out of the euro,’ the narrative goes. It can get extremely hyperbolic like France’s Left Front leader Melenchon arguing that the “German government is destroying Europe” for the third time in a century, conflating tens of millions of deaths with the end of an illusion that even modest social-democratic politics could coexist with the European Project. This doesn’t sound like a left learning from five years of experience.

The stance of Germany and other so-called creditor states rightly provokes outrage but it can hardly be considered a betrayal of Europe. Germany’s stance is aligned with the euro drafted in the Maastricht treaty: a currency union without fiscal transfers between member-states and limits on debt and deficits. The whole response to the outbreak in 2010 of the sovereign debt crisis has been an effort to reinforce that exact model for the euro. It’s of course a disastrous model that produces enormous economic suffering in the periphery, but it’s the model periphery countries signed up for and rule out leaving. The outrage committed by Germany has been the injection of national chauvinism promoting stereotypes of work-shy southern Europeans. This, coupled with the moralism of repaying the debt and fiscal discipline, builds up dangerous economic grievances framed on national lines.

This is where the permanency of the defeat in Greece becomes evident. Syriza for months witnessed the rigidness of the Euro Zone on debt and fiscal policy. It then called a referendum and locked in some of the costs that would come with a euro-exit like rationing bank notes, disruption to Greek industries, and a political crisis involving rival pro-govt and anti-govt demonstrations. Having endured some of the economic damage that would come with a Grexit, Tsipras doubled down on negotiations with creditors who then extract harsher conditions. This isn’t a retreat to regroup, this is the acceptance that there’s no alternative to being administrators of a creditor vassal state.

The situation offers a golden opportunity for Europe’s far-right. Right-wing and xenophobic euroskeptic parties can champion themselves as the only political force that is capable of saying no to the authoritarian liberalism of the European project. ‘The left is ideologically compromised’, they will argue, ‘choosing to keep intact the European Project rather than defend their voters from creditor impositions’. The far-right will get the chance to end the monetary union on their terms. The last humiliation for Europe’s left will be the emotional blackmail to close ranks with the EU to halt the far-right’s advance.

Europe’s Existential Crisis in Greece

Short of sending the gunboats, it’s difficult to imagine anything more Greece’s creditors could’ve done to intimidate voters into accepting the austerity ultimatum presented to their government. The weekend the referendum was announced, The European Central Bank froze support to the Greek banking system, forcing the government to impose capital controls. It’s a distressing experience losing a wallet, imagine being locked out of your bank account? That’s been Greek life for a week with a limit of sixty euros in daily withdrawals. On top of this, in a coordinated move European leaders made appearances or released statements saying a no vote in the referendum would mean a Greek exit from the common currency. To complete the blitz of intimidation, the Greek media and much of the international media took photos of every bank queue and empty shelf, all while circulating any rumor.

Despite all this, 61% of Greek voters delivered a resounding no on Sunday, painting the entire Greek political map one single color rejecting imposed structural adjustment. Hopes were suddenly dashed across European capitals and EU institutions for a yes vote that could pave the way for a technocratic government that would obediently implement whatever creditors proposed. European authorities are incredulous that after five years of telling Greeks that austerity was the sacrifice necessary to stay in the euro, Greek voters don’t believe another year and a half of cuts and tax increases will guarantee their membership.

This puts the whole European project in a moment of existential crisis. If it doesn’t accommodate Greece and continues using notionally independent institutions like the European Central Bank as a siege weapon on the Greek economy, it provides all the ammunition necessary for euroskeptic political forces to tear the project to sheds over the next decade. Alternatively, if Europe makes meaningful concessions to Syriza, it risks an electoral storm sweeping the south of Europe with elections this fall in both Portugal and Spain.

The designation of Alexis Tsipras as a radical and a threat to the European order speaks to the terror felt by Europe’s geographic and political center over any attempt to alter economic policy. Syriza has sought to renegotiate the 2010-2012 crisis response of deficit limits, austerity as precondition for “solidarity” loans, and full repayment of the debt. Creditors were able to extract these concessions from Europe’s periphery as the alternative, they argued, to expulsion from the euro and financial collapse. The streets of Europe resisted this settlement through social movements in 2011 and a pan-European general strike in 2012. Out of these social movements, parties like Syriza and Podemos would find a significant political base to build upon.

European leaders applaud themselves and the austerity regime for ending the financial crisis yet this is an outrageous act of historical revision. Forcing out Berlusconi and replacing him with Mario Monti, an unelected technocrat, didn’t end the sell-offs in Italian bond markets in 2011 and 2012. Only the intervention by European Central Bank president Mario Draghi to do “whatever it takes” ended the sell-off. Italy and Spain, with the backing of the ECB, avoided the full bailout programs seen in Portugal, Greece, and Ireland, but by then the social damage across Europe’s periphery was already done.

Seven years after the world financial crisis of 2008 double digit unemployment persists across Europe’s periphery (over 20% in both Greece and Spain), unemployed youth continue to emigrate en masse, a suicide epidemic has taken hold, and education and healthcare funding have been slashed. Opponents of austerity have rightly called this a humanitarian disaster that requires policy action to restore electricity and undo pension cuts for the most vulnerable. This is what Syriza was elected to do, and this is what European authorities consider incompatible with the European project.

Fear of an axis of leftist governments on Europe’s periphery left creditors with a perverse incentive in negotiating with the newly elected Greek government: they had to make offers Syriza couldn’t hold up as a victory. The talks went on for five months and concessions by Syriza weren’t matched by anything more than lower primary budget surplus targets, something regularly conceded to other crisis affected countries. Renegotiating the Greek debt burden stayed completely off the table while creditors insisted upon the Syriza government introducing pension cuts and tax increases, forcing the party’s fingerprints onto the austerity dagger.

Syriza thought it would have a better bargaining position in negotiations given the potential financial contagion from what would be the biggest sovereign debt default in history. It hoped to win support of center-left governments in Rome and Paris in negotiations, allowing it the policy space to implement a sort of humanitarian Keynesianism in Greece to address the worst human suffering from five years of austerity. But France and Italy were more interested in squeezing out what’s left of the post 2008-2009 global economic recovery than risking an open clash with Europe’s austerity regime.

This all now leaves Europe in a very dangerous position in the next few days, months, and years. In seeking Syriza’s total capitulation it may force the Greek government to reintroduce the Drachma. Punitively forcing Greece out of the Euro would make the European project permanently toxic for the left across the continent, leaving just the eroding political center to defend it. The sympathy toward Syriza by some in the Portuguese and French socialist parties speaks to how extensive the damage could be. Should Alexis Tsipras take Greece out of the euro he’ll be denounced as the radical who broke Europe, but the truth is this is a catastrophe by Europe’s extreme center; let them own it.

From 15M to Elections: The Left-Wing Forces Threatening The Old Guard of Spanish Politics

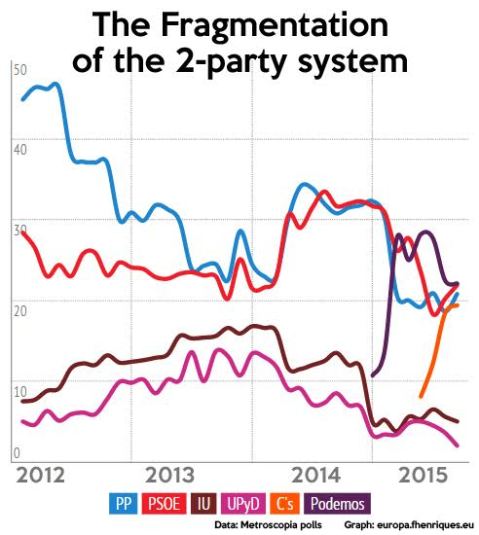

Spanish regional and local elections in May saw a variety of leftist forces achieve unprecedented results at the expense of the traditional center-left and center-right parties. These advances for the left come precisely four years after the 15M movement occupied squares in towns and cities across the Spanish State, ushering a new wave of contentious politics that continue on in different forms and mobilizations to this day. 15M initiated the steady decline of the two party system that alternates power between the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) and the People’s Party (PP). When the People’s Party won the 2011 elections only to continue and deepen the austerity started by PSOE, 15M in the streets offered an alternative, sincere opposition to the one put up by the Socialists. The protesters would brand the two parties PPSOE, a single corrupt and unrepresentative entity, condemned to see their support drop over the next three years.

While it’s tempting to declare Podemos, the municipal election platforms, and other leftist formations the electoral expression of 15M, it’s more accurate to call them the movement’s consequences, both in filling the political space created by 15M and in tapping its grievances with the economic and political system. Podemos, Barcelona en Comú, and Ahora Madrid each sought tens of thousands of signatures from the public endorsing their vision, verifying a clamor for their project taking the next steps towards elections. The consequences of 15M on these new political formations manifest in other ways, like statutes limiting the income of elected candidates, refusing bank financing, and mandating the publication of donations and their contributors; the statutes themselves being debated and decided in assemblies.

These sort of measures have a populist appeal to a public hostile to politicians, but that doesn’t mean they don’t fill a need. There’s a systemic level of corruption in Spain, best exemplified in the case of the People’s Party’s treasurer, Luis Barcenas, who operated a slush fund that directed secret contributions from private contractors to elected party officials, including the current prime minister Mariano Rajoy, according to documents leaked to the press. In Catalonia, the ruling center-right coalition CiU faces a similar scandal and just had fifteen party headquarters locked down as part of a corruption probe. The Socialist Party has been tarnished by corruption cases as well, and in the Madrid region, board members appointed across the political spectrum (including trade unions and United Left) to manage public savings bank Caja Madrid were found to have spent 15 million euros in undeclared company credit on personal expenses. The savings bank would later be merged into Bankia, a bad bank that would receive 22 billion euros in public assistance.

The Podemos Eruption

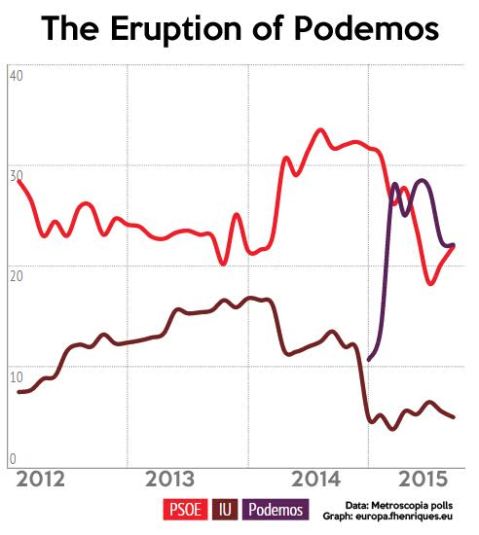

Podemos found a working formula in 2014 when it vastly exceeded pre-election polling for European elections, winning 8% of the vote and five seats compared to the single seat widely projected. Going into the elections it wasn’t obvious where Podemos would find a base of voters.United Left had been improving in the polls through 2012 and 2013. Despite concerns from activists about United Left‘s appropriation of 15M, it remained the political actor best placed on the left to benefit from the Pasokification of PSOE.

The European elections. however, showed how United Left had been failing to draw in dissatisfied voters. Though United Left came ahead with 10% of the vote, Podemos manage to tap into a wider segment of population. In the months following the elections, as exceeded expectations compelled news coverage and brought many thousands of new participants into the informal party assemblies known as circles, Podemos blew past the ceiling United Left had struggled to break and began rivaling and even surpassing PSOE as the largest formation on the left.

Podemos approached politics with a high sense of social urgency, an approach that contrasts with a party like United Left too often resigned to and satisfied with an improvement over previous electoral performances. It’s difficult to ask voters to back a left-wing formation in the hope that in two or three election cycles it may become an option to govern. Podemos’s goal was to build support among the existing “social majority” opposed to austerity and frustrated by the failures of the two party system. It would try to discard recognizably left-wing symbols and terminology to avoid alienating parts of this social majority, though the presence of republican tricolors at party events suggests its base remains anchored in the left.

But one of the most widely cited explanations for Podemos’s success gives credit to Pablo Iglesias’s access to highly watched political debate TV programs and his ability to tap into that righteous anger which has brought millions out into the street; there’s dozens of videos of him on Youtube with hundreds of thousands of views for a reason. The recently departed Podemos leader Juan Carlos Monedero, and close friend of Iglesias, went as far as comparing television appearances to the German train that transported Lenin from Switzerland to Russia. Crucially, he went on to add that at some point one has to get off the train.

Monederos’s comments and departure speak to the loss of confidence in Podemos from months earlier when it reached first place in a number of opinion surveys. Podemos’s peak came after last autumn’s foundational congress where Iglesias and his allies like Monedero argued strongly for a centralized party form with the traditional position of secretary-general. Their point was that only a central figure could finish what Podemos started, while a decentralized formation with spokespersons would debilitate it. Iglesias famously said “you don’t storm the heavens by consensus, but by assault.” The centralized model prevailed over one that devolved authority and autonomy to the circles. Having got the party model he wanted, Iglesias would go on to easily win the position of general secretary with 88.6% of the vote from membership .

The Limits of Podemos

The first months of 2015 would shake the confidence in Podemos. The quick rise of the center-right Ciudadanos would challenge Podemos’s monopoly on the anti-corruption message, even though Ciudadanos was a party that had existed in Catalonia since 2007 as an opponent of Catalan nationalism and an advocate of a centralized state. Ciudadanos was offered as an alternative to those frustrated with PP and PSOE but were weary of trusting Podemos, a party that was subjected to increasing attacks by opponents associating it with Venezuela and ETA.

In March Podemos got its first test since European elections in the most populous region of Andalusia. Andalusia is a bastion of the left that has been dominated by PSOE since the end of the Franco dictatorship. It’s also where United Left had won 11% of the vote in 2012 and had been gaining further support up until the formation of Podemos. It’s ones of the places where Podemos has to run up the vote if it wants to be the primary force in Spanish politics, let alone achieve the majority Iglesias has expressly desired. The 14.8% Podemos won in March was a large improvement over the 7.1% they took in Andalusia in 2014 European elections, but it left them far from where they want to be: ahead of PSOE, which took 35% of the vote.

The Andalusian elections humbled expectations for a party that weeks before had aspirations of repeating what Syriza achieved in Greece. In Athens they chanted in Spanish “Syriza, Podemos, we will prevail!” It’s a tall order to climb down from dreams of a rupture with austerity across the south of Europe, but it something Podemos supporters and Iglesias himself appeared to be bracing for. General elections at the end of 2015 may not give Podemos a victory, but force it into a long-term strategy that both competes against PSOE and partners with it to prevent PP from maintaining power with the support of Ciudadanos.

The Triumph of Left-wing Municipal Initiatives

Local and regional elections in May would lift expectations as left-wing formations took well over 20% of the vote in four of the five biggest cities, giving them the best position to lead the new city administrations. This wasn’t a story about a Podemos victory, though. Podemos last fall decided not to run in city elections after popular municipal initiative Guanyem Barcelona (later known as Barcelona en Comu) formed in the summer and was being quickly replicated in a number of other major cities. The voter overlap between Podemos and these municipal initiatives were obvious. Fearing a poor result in local elections, Podemos would participate in these municipal platforms, only running under its own name and logo in regional elections.

The contrast between the performance of Podemos in regional elections and that of municipal formations in key contests is subject of enormous debate and discussion in the last two weeks. At one end, you have those who point to the success of Ahora Madrid and Barcelona en Comu and calling for this model to repeated for general election; this argument is being pressed by voices both inside and outside Podemos. At the other end, you have some in Podemos, notably Pablo Iglesias, pointing to a number of places where the Podemos name and logo outperformed municipal formations.

It’s a debate difficult to settle by numbers because there were places like Catalonia and Galicia were only city elections took place. And while there were many attempts to replicate Barcelona en Comú, in many cities these platforms failed to encompass the bulk of forces to the left of PSOE, and in a number cases, there were even competing municipal formations on the left with similar names, to further confuse the matter. That said, it’s difficult not to be persuaded by the idea popular unity for general elections, seeing the results in the city of Madrid where Ahora Madrid got 519,210 votes (32%), compared to the 286,973 votes Podemos got from the city in the election for the regional assembly. Ahora Madrid left PSOE just 15% of the vote, relegating the socialists to a junior partner in a coalition government.

The position of the most successful municipal left formations contrasts with Podemos in regional parliaments where in every case it can at best hope to be a junior partner in a coalition led PSOE; that or a political pact that permits a PSOE minority government. Reflecting on this post-election landscape, Pablo Iglesias spoke of the need to make Podemos a party opened to other left forces to enter and strengthen it, but this reading is insufficient and plays into anxiety that Podemos is out for hegemony. It’s a reading that puts Podemos at risk of being outpaced by events much like United Left was in 2014.

Left Plurality, Not Just Unity

There is already an effort to replicate the success of Ahora Madrid and Barcelona en Comú for the general elections. So far, it’s Alberto Garzon, the young and popular MP from United Left, who is pressing the case for unifying forces to the left of PSOE. This is not the first time, however, United Left has made such a appeal. It made a call for a popular front after Podemos’s strong performance in European elections . Then, Podemos dispensed the idea with good motives as it was enjoying political momentum that may have been weighed down by what Iglesias calls an “alphabet soup” of political acronyms. This isn’t nearly as persuasive after the May 24th elections.

As difficult as getting Podemos and United Left under a shared formation may be, it’s not sufficient if the goal is to truly repeat the confluence achieved in cities like Madrid, Barcelona and Zaragoza last month. Only five of Ahora Madrid’s twenty city councilors are Podemos members, the rest are independents, United left defectors, from Ecosocialist Equo, or members of Ganemos Madrid, the original municipal formation organized in summer 2014. You’ll find a similar story with Barcelona en Comú which was headed by an independent housing activist Ada Colau; only two of the ten councilors joining her come from Podemos. This speaks to the depth of participation that took place in these municipal formations.

Trying to make a functional assembly based electoral platform for a small geographic unit like a city is extremely ambitious, to attempt it across an entire country with a much smaller window of time before elections is a monumental task. Existing political parties would presumably have to carry a greater load in initiating the process, but they would have to be restrained from limiting it to a negotiation splitting an electoral list among themselves. To make popular unity a mere coalition of parties would exclude activists and campaigners who offer invaluable knowledge and experience from fighting home evictions, unearthing corruption scandals, building self managed spaces and countless other struggles that have blossomed out of 15M.

Popular unity would also have to encompass the territorial diversity of the Spanish state. Some of the strongest performances in May elections were put up by left nationalist formations: Compromis in Valencia; MES in the Balearic Islands; Geroa Bai and EH Bildu in Navarre; and CUP and ERC in Catalonia. To win the general elections, or have any hope of approaching a majority, a formation of popular unity must attempt to include these parties, or at the very least, embrace the aspirations of their voters for self-determination, for greater self-rule and for an end to the Spanish state’s imprisonment of political dissidents in the Basque Country.

The challenges for a formation of popular unity are immense, but the benefits would be too. In the months leading up to general elections, this formation could repeat the assemblies and neighborhood engagement the municipal platforms did so successfully. It could recapture the enthusiasm and participation that marked 15M, Podemos’s high point last year, and the weeks leading up to local elections last month. A formation of popular unity is the only viable alternative to either PSOE or PP returning to power, a result that would continue the social, territorial and economic crisis of the post Franco regime and maintain Syriza’s total isolation in Europe.

The Revolt of the Ladders: The Technicians Challenging a Telecommunications Giant

Since early April technicians for telecommunications giant Telefonica have maintained an indefinite strike across the Spanish state over their precarious working conditions. Their cause could hardly be more just. Thousands of these technicians are subcontracted, facing 10-12 hour days, no holidays, the responsibilities for their own transportation and equipment, all for as low as 600-800 euros a month. It’s under these circumstances in which a militant, indefinite strike has broken out in an election year that has the ruling Popular Party selling precarious job creation as an economic success story.

The strike was started by technicians in Madrid on March 28th in response to the contract proposed by the company that decreased pay scales. The strike achieved widespread following in Madrid with upwards of 90% adherence according to the strike committee. On April 7th, the infinite strike expanded to provinces across the Spanish state with similarly high adherence. Information pickets were maintained and company offices and stores became the sites of demonstrations by workers and their supporters. Within days Telefonica would withdraw the proposed contract, but the indefinite strike would go on as the workers weren’t seeking the continuation of their miserable conditions, but genuine relief.

RT gabalaui: 1º de mayo con la CGT: La huelga de los técnicos de Movistar sí existe #ResistenciaMovistar pic.twitter.com/d0LXiaJctA

— CGT_Rotocobrhi (@CGT_Rotocobrhi) May 1, 2015

The Telefonica-Movistar technicians are demanding eight hour work days and to be integrated into the salaried workforce of the main company where wages are twice that currently received by some 20,000 workers employed through subcontractors. It’s a set of demands that doesn’t speak to the modesty of the workers but to the severity of exploitation in 21st century capitalism, a 21st century capitalism where workers find themselves engaged in labor battles previously fought and won.

At the other end of exploitation are the vast profits earned by Telefonica two decades after its privatization by the Popular Party. The reduction of 50,000 fixed jobs has turned Telefonica into one of the highest earning Spanish enterprises, bringing in over three billion euros in profits in 2014 and four and a half billion in 2013. All of this drives the strikers to deepen the strike in both its duration and militancy. Strikers have maintained pickets at company facilities and have allegedly carried out sabotage on the telecommunications network, 800 separate acts sabotage according to the company, accusations that fueled a police crackdown with the arrest of sixteen workers. The strikers demand their release and the dropping of charges, arguing that the alleged sabotage of the telecom network is in fact severe neglect by the company and represents a danger to the technicians attempting to repair it.

While pickets and alleged sabotage have a deep history in labor struggle, this strike has seen workers utilize new tools. Whatsapp, Twitter and other social media sites have made up for the lack of interconnected labor organization across the Spanish state. Through a popular strike blog, assemblies and mobilizations are scheduled for workers and their supporters to keep tract of the struggle and to participate. Without the backing of the two main trade unions, UGT and CCOO, the workers appeal for support to their crowd-sourced strike fund that’s prioritized to the families in deepest need.

The role of both CCOO and UGT in the technicians strike has been particularly shameful. Weeks into the strike the two trade unions called their own two day weekly strike. The two unions then entered into an agreement with the company, bypassing the self organized workers and smaller unions who’ve done the heavy lifting. The striking workers have denounced the actions of CCOO and UGT as a naked attempt to unravel the strike before its demands have been met. Slogans like “we fight, we negotiate” have featured prominently in the protests. Union offices have been surrounded by angry workers and struck with eggs, flares, fireworks and other missiles.

Así han quedado las sedes de los sindicatos de la patronal CCOO y UGT por traicionar a #resistenciamovistar Seguimos. pic.twitter.com/NwbIOOZLni

— Informática CGT (@Informatica_CGT) May 7, 2015

The combativeness of the strike was further demonstrated when workers and their supporters occupied the company headquarters at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, forcing Telefonica to concede negotiations with the workers collective. The company, however, showed no good will in the negotiations, having the meeting place flanked by vans of riot police and insisting workers have to negotiate wages and conditions with the third party firms contracted by Telefonica and not the company itself. The occupation nonetheless brought the workers recognition and showed how the deal with CCOO and UGT was just a ploy to undercut their struggle.

La persistencia y lucha de #ResistenciaMovistar obliga a Telefónica a negociar. No bajemos la guardia y sigamos. pic.twitter.com/CqaOpn76TW

— Informática CGT (@Informatica_CGT) May 10, 2015

While we don’t know if the revolt of the ladders will achieve its goals, it represents an important evolution of the labor movement. Workers are increasingly opting for the support and backing of smaller unions, like the anarcho-syndicalist CGT as well as AST, CO.BAS in the case of Telefonica,The hope is that this is just the beginning of the moderate trade unions being displaced. This autumn left-wing parties, social movements associated with 15M, and smaller trade unions will make the unprecedented effort of organizing a general strike across the Spanish State. If successful, they would be taking a powerful political tool out of the hands of CCOO and UGT union bureaucrats who’ve worked to contain unrest over austerity just as they tried to contain the revolt of the ladders. A victory for the technicians of Telefonica would pave the way to this popular general strike.

Catalonia lurches into the unknown after high court suspends referendum

If at the beginning of this year, I had marked out the predictable events in Catalonia’s bid for independence, the suspension of the independence referendum by the constitutional court on Monday, September 29th, would’ve been the final one. It wasn’t surprising that gigantic crowds would protest for independence on the 11th of September. It wasn’t surprising that the Scottish referendum would be wielded by Catalans to make their case that the right to self-determination can be applied peacefully and democratically. Lastly, it wasn’t surprising that the Spanish government would move at the highest speed to suspend the efforts by the Catalan government to hold a vote on independence. The exact dates would’ve been hard to pin down but the order unmistakable. It was a plot you could read out chapters ahead, but then with total abruptness, the climax is totally out of sight.

Now one must ask an unanswerable question: What happens when hundreds of thousands of people who are deeply committed to seeing Catalonia’s independence aren’t even allowed a non-binding vote? To get an idea, it’s worth remembering that Catalonia has been intensely debating its relationship with Spain for a decade now, going back to the autonomy statute in 2006 that was scaled down by this same constitutional court in 2010. This disappointment is a crucial part in the rise of independence sentiment over the last few years, a rise overly attributed to the economic crisis by the international media. Catalan aspirations for self-rule can only suffer so many setbacks before the rupture between Catalonia and the Spanish state becomes complete. The ruling Spanish conservative party seems indifferent to this risk.

There’s another crucial aspect to what’s happening in Catalonia. The pro-referendum forces are a majority in the regional parliament, but it’s the most awkward arrangement (they’re not formally in government together) between center-right Catalan nationalists and three left parties that consist of the republic left, eco-socialists, and the gloriously far-left party CUP which explicitly calls for the independence of not just Catalonia but of all the “Catalan Countries” on either side of the French and Spanish border, as well as supporting open borders and the liberation of migrants held captive by Spanish immigrant detention facilities. The only thing holding this Catalan parliament together is the prospect of a referendum; take the referendum away and you in all likelihood have snap elections that will measure the extent of the rupture I just mentioned. If the past nine months went according to script, the next nine months are a leap into the unknown.

Catalonia’s Quest for Self-Determination

We are three months away from a planned referendum in Catalonia that will ask voters two questions: “Do you want Catalonia to become a state?” and if yes: “Do you want this state to be independent?” If only things were so straight forward. Catalonia’s self-determination is strongly rejected by Spanish authorities who refuse to recognize the planned referendum and are fully intent on stopping it from happening. That the regional government has risked this confrontation with the Spanish state is due to the mass movement by Catalan civil society that has made any other political calculation impossible. Spanish authorities refuse to acknowledge this immense democratic desire by millions of Catalans to determine their country’s status. In doing so, these authorities are risking an irreparable rupture between Catalan society and the Spanish state if all avenues remain closed to a democratic vote.

This effort to have a referendum on self-determination goes as far back as 2009 when the small municipality of Arenys de Munt hosted its own vote on independence. Later that year, more than a 150 municipalities in Catalonia followed Arenys de Munt’s example. By the latest count, some 697 municipalities adhere to the Association of Municipalities for Independence. This campaign was strengthened in part by the 2010 ruling by the Spanish constitutional court that struck down or altered fourteen articles in Catalonia’s autonomy statute and provided its own interpretation of 27 others; many of these articles are sensitive to Catalan ambitions for self-governance like the power to tax, language use, not to mention ruling against the definition of Catalonia as a nation in the statute’s preamble. The week after the ruling an estimated one million people took to the streets of Barcelona to protest the court’s decision, bringing together a broad section of Catalan society including trade unions, FC Barcelona and most of the parties represented in the regional parliament.

The ruling convinced an increasing amount of Catalans that a glass ceiling on autonomy had been reached within the current post-Franco framework of Spain and that independence had become the only path to the self-governance. This shift in Catalan society was made evident in 2012 when as many as one and a half million people protested in Barcelona in a demonstration explicitly demanding independence from Spain. Opinion surveys show that 46% of residents of Catalonia want independence versus 36% opposed. Significantly, the consensus on deciding this by referendum is broad, with 74% demanding that the Spanish prime minister recognize the November vote.

Enter Spanish Nationalism

Just as aspirations in Catalonia for independence mounted over the past few years, the Spanish nationalist Popular Party came to power in general elections in 2011, riding voter rejection of the Spanish socialist party amid austerity and eye-watering levels of unemployment. The Popular Party, which while in opposition challenged the Catalan autonomy statute in the supreme court, would continue its role as chief antagonist in government. This antagonism to Catalan aspirations and identity was best illustrated in comments by the conservative education minister Wert when he said his goal was to make Catalan students more Spanish. It wasn’t just a provocation in words, the government passed an education reform bill that triggered over a year of protests and two general strikes by teachers, parents, and students. The opposition was extensive in regions like Catalonia with co-official languages, as the law makes it obligatory for regional administrations to offer Spanish as a language of instruction. This represented a second blow to the autonomy statute which affirmed Catalan as the language of instruction in schools.

There is a remarkable level of complacency about this worsening relationship between the Spanish state and Catalonia. The Spanish government holds firm to its rejectionist stance, repeating the indivisibility of the Spanish nation and the illegality of the referendum. It will cynically suggest that advocates of Catalan independence achieve the 3/5ths majority in both houses of the Spanish congress to change the constitution; the Popular Party controls both houses and objects to Catalonia’s current level of autonomy and would in no way cooperate in reforming the constitution to either expand autonomy or create a democratic mechanism for peaceful succession from Spain.

This is the dialogue of imposition. While a vast majority of residents in Catalonia want a referendum this November, Spanish prime minister Marino Rajoy insists he won’t let the referendum take place. It’s a naked attempt to deny voters in Catalonia an opportunity to express themselves on the sovereignty debate while allowing the Spanish government to avoid the political consequences of a likely yes vote for independence. Spanish conservatives are well accustomed to downplaying and dismissing mass protests like the ones for independence in Catalonia. They can write them off as a concentration of radicals out of touch with the silent majority that the Popular Party is so quick to cite. The referendum could shatter this argument and end the deference on Catalonia currently offered to the Spanish government by the European and international community. Spain would risk holding on to Catalonia against the will of a majority of its inhabitants, an unsustainable policy which has tragedy written all over it.

Knowing this, the central government hasn’t limited itself to just endlessly repeating the illegality of the referendum, it is actively using scare tactics and veiled threats to weaken the independence vote. Government ministers and leading Popular Party lawmakers paint dire scenarios of an independent Catalonia outside the alleged safety of the euro zone, the European Union, and Nato while economically crippled from the loss of trade with Spain. These aren’t warnings, but threats, for these scenarios would only happen if the Spanish government acted out in vengeance against an independent Catalonia by severing trade and blocking attempts by the new state, if it so desires, to remain part of those international and European treaties and unions.

Political Rupture

The opportunity to persuade Catalan voters to avoid independence might have been missed this June when tens of thousands took to the streets in a tide of republican tricolor flags at news of the king’s abdication and prince Felipe’s ascension to the throne. The protests extended across the territory of the Spanish state, including Barcelona, where Spanish and Catalan republicans demonstrated in the thousands for the end of the monarchy. Many of those protesters had hopes of a constituent process as a second transition to democracy and a federalized state.

Así estaba esta tarde la Puerta del Sol de Madrid. Miles de personas reclamando #ReferendumYA #YoPidoReferendum http://t.co/txXK1jseTY—

Izquierda Unida (@iunida) June 07, 2014

These demands from the street for a referendum on the form of government were ignored much like demands in Catalonia for a referendum on independence. The political system that emerged following Franco’s death has shown itself unbending to a society that has been pulsing with popular, mass demonstrations and a hunger for a deeper democratic process. It is no surprise then that this system is in danger of breaking, standing to lose 17% of its population from Catalan independence and possibly more should the Basque Country choose to secede as well.

The political ruptures aren’t just geographic, however. The liberal Catalan nationalists CiU who’ve governed the region for most of its post-Franco history have hitched themselves to the campaign for independence but they’ve failed to win back political ground lost after implementing unpopular austerity measures over the last several years. Now adding to their problems, Jordi Pujol, former CiU leader who governed the region for 23 years, has admitted to having stashed away a fortune of 600 million euros in Switzerland. Meanwhile, the forces on the left cooperating with CiU on the referendum are the ones reaping the political rewards; The Republic Left of Catalonia came in first place among Catalan voters during May’s European elections.

What an independent Catalonia would look like is still to be decided and those supporting independence as a simple administrative rearrangement may end up disappointed. Catalan politics has no shortage of political initiatives and social movements seeking to alter the governance of the country, come independence or not. The left-wing CUP (Popular Unity Candidates) has been campaigning for independence with the slogan “yes, to change everything”, insisting there isn’t independence without popular, democratic sovereignty over economic life. In Barcelona, there’s been a summer of neighborhood assemblies as part of Guanyem Barcelona (win back Barcelona), a citizen initiative that seeks the highest form of democracy and self governance for the city while both restoring and expanding of social rights.

The Coming Crisis

This summer and fall should have been a time of vibrant debate in Catalonia on the questions voters would answer in the November referendum. In the absence of this debate, there’s the growing impression that Catalonia and Spain are sleepwalking into a crisis in which the key actors have irreconcilable differences. There is no common ground between supporters of the referendum seeking a democratic outcome and the opponents who seek their total capitulation.

The political bloc behind the referendum is showing fractures under this pressure. The governing center-right CiU is divided and the splits are becoming more public in expectation of the Spanish constitutional court ruling against the regional government’s law facilitating the November referendum. The Democratic Union of Catalonia within CiU is opposed to hosting the referendum should the constitutional court stand against it. Pro-independence organisations, parties on the left and other voices within CiU insist on hosting the vote regardless of the high court’s decision. Whether this pro-referendum bloc can hold together until November will determine whether the sovereignty crisis comes to a head this fall or delayed into 2015.

The next few weeks and months will be of the highest importance for Catalonia’s future. On September 11th, the Catalan national holiday, hundreds of thousands are expected to demonstrate in Barcelona, forming a giant V to symbolize the right to vote and a victorious result for the pro-independence bloc. The following week, the Catalan regional parliament will put forth its law of consultations, paving the way for the November referendum. The scenarios from there range from civil disobedience, should Madrid try to prevent a vote, to snap regional elections as a substitute for the referendum. These events aren’t a curiosity of Spanish politics, but moments of historic consequence for Catalonia, Spain and the European continent.

Europe: Don’t mourn the collapse of the political center

The National Front’s election triumph is the long shadow cast by the broken aspirations left by the Socialist Party’s victory in 2012. The French Socialists had Hollande in the Elysee palace, control of the legislature and a continental mandate to break the austerity regime that Merkel and Sarkozy had enforced. Two years later and Hollande’s second prime minister has just passed another 50 billion euro austerity package. It’s a story of governing having consequences and Marie Le Pen’s right-wing nationalism offering itself as the political reckoning.

The French socialists are not isolated in their fate. It doesn’t take long to see the wreckage of the former political giants of social democracy strewn across the continent. PASOK, which in 2009 took 43% of the vote in general elections, won just 8% support from Greek voters this weekend, condemning the party to the role of New Democracy’s sidekick in the coalition government. In Spain, Alfredo Rubalcaba of the Spanish Socialist Party has conceded to a change in party leadership after the party’s dismal performance Sunday. In Portugal, the Socialist Party faces its own leadership questions after beating the center-right coalition by a disappointing margin of less than 4%. Even after nearly three years in opposition to deeply unpopular center-right austerity governments, Spanish and Portuguese socialists still can’t convince voters to reward them with power, let alone a majority.

While the socialist parties of Europe collectively suffer from a shared crisis of reconciling their commitment to the European project with the social democratic convictions of their base, the advance of the far-right on the continent doesn’t offer such a unified reading. In places like Austria, the 20% share won by the Freedom Party returns the party to strength it previously had. In Greece, Golden Dawn’s won 9.4%, after only winning half a percent in 2009, carving out a new space in Greek politics for a party that has verified its fascism with a violent, murderous campaign against leftists and migrants.

We don’t have to paint all these far-right, right-wing nationalist forces with the same brush in order to fully despise their politics, nor should we scapegoat them for the continent’s xenophobia. After all, it was Spanish police who earlier this year fired rubber bullets and tear gas at migrants swimming to shore. Over a dozen migrants drowned and the actions of the police were defended by the conservative interior minister who threatened those criticizing the police with legal action rather than launch an investigation into their conduct. Golden Dawn would surely envy the opportunity to commit such an atrocity with impunity.

Europe’s center is hardly suited to defend democracy from existential threats like Golden Dawn. Who could forget the technocratic governments installed in Greece and Italy? Mario Monti and Lucas Papademos were made prime ministers without so much as a single vote being cast for them in either a constituency or for a party list that carried their names. But those who would today offer themselves as defenders of democracy shrugged this off as a typical government reshuffle between elections or “national salvation”. When there weren’t technocratic governments, there were memorandums by the Troika (European Central Bank, IMF & European Commission) imposing policy measures in Ireland and across Southern Europe.

By no means am I arguing that the success of far-right parties has no consequences. The National Front would use the discontent over austerity to break apart Europe along nationalist lines. The existing divisions between debtor and creditor states already fan nationalist grievances, a dangerous political device that the far-right aren’t alone in tapping. Narratives portraying the nation as a victim leave little room for minorities or forces which prefer social conflict among classes. It’s easy to unleash nationalism, far more difficult to restrain its passions.

At the end of a right-wing nationalist break-up of the European project, would those who suffered from the effects of EU imposed austerity be better off? I fully Doubt it. It’s here where the social movements from 2011 have made a difference. The success of Syriza in Greece and several left-wing parties in Spain can’t possibly represent the political content of those protests, but they are a consequence of those demonstrations. Crucially, they’ve created political space for those who despise the far-right and don’t wish to close ranks around the centrist parties who are responsible for so much of the misery across the continent. Nationalism or austerity is a false choice, but it must be defied by building another Europe that has no place for razor-wire fences, Troika memorandums, or Marine Le Pen.

The Markets Recovered But Social Peace Hasn’t Been Won

Since global capitalism plunged into existential crisis in 2008, workers, students, pensioners, and other vulnerable segments of society have mounted mass protests in the face of a grinding neoliberal policy offensive that has hiked tuition, privatized services, dismantled labor rights, and slashed wages and benefits. The millions who protested from Lisbon to Athens, London to Wisconsin, and countless other places were for the most part ignored. The defeat of these protests has real consequences, however, and it has taken a rising toll with each passing day. Tens of thousands in Spain are still being evicted from their homes each year, record unemployment in Southern Europe has left behind a permanent, swelling underclass, and a generation struggles with choosing between dependence on their parents well into their late 20s or early 30s, or exile to another country in search of work that may or may not sustain them.

With the mass street protests largely exhausted, global stock markets euphorically rallying to record highs, and profits and income gains being registered by the most privileged sectors of society, politicians who’ve governed since the crash are desperately trying to cash in politically on this unbalanced recovery. The risk is if this triumphalism ruptures the bitter resignation of much of the public who saw little alternative but to trust the narrative that the measures are temporary, and that contesting them would only heighten the state of emergency. This narrative is already being walked back by Portuguese prime minister Passos Coelho, who has acknowledge that levels of pay and benefits won’t return to pre-crisis levels, and instead, effort will be put to making pay cuts permanent.

We have found ourselves in an age when social-democracy has no policies or political aspiration. Europe’s socialist parties can do no better than promise to carry out austerity with less enthusiasm than their center-right rivals. The state of Europe’s center left is so bad they look on with envy across the Atlantic at Obama’s policies like healthcare reform. What a sad state of affairs when the most half-hearted, business friendly attempt at reforming the U.S. healthcare system makes the U.S. Democratic Party the standard-bearer of social democracy across the globe.

Contesting the ideological bankruptcy of the dominant political parties is left to those same social movements that suffered repeated failures in their goals of altering the crisis policies of center-left and center-right governments. Failure isn’t the same thing as being wrong, though. The critique of the movements that occupied Puerta del Sol in Madrid or Syntagma Square in Athens still have a better analysis of current state of affairs than any parliamentary force. The system may not have failed and come crashing down as authorities warned but it still failed the poor and working class, leaving older generations with reduced wages or pensions, and condemning the young to precarious work, exile or both.

In Spain, there are positive indications that the collectives, platforms, and social movements that rallied huge protests in 2011 and 2012 are reemerging with new, contentious politics; contentious politics that not only object to the political ambitions of the two dominant political parties, but to offer their own political ambitious to rectify the injustices in Spain. For the past week, Marches of Dignity have set off from each end of the Spanish state, marching dozens, even hundreds of kilometers to reach Madrid by Saturday. The Marches of Dignity brought together some 300 collectives, from anti-foreclosure groups, to the most left-wing unions, as well as platforms by indignados that previously carried out separate mobilizations.

What stands out about this mobilization is that it managed to bring these platforms, unions, and collectives behind a shared set of demands: bread, housing, dignified employment, and a basic income. It’s a set of aspirations that is essential to breaking widespread resignation and giving protesters an objective to tirelessly strive for. It’s insufficient and undesirable to return to the state of affairs before austerity. Society was broken and unjust before austerity and that can’t be forgotten. Instead, these aspirations not only reverse the misery brought by austerity but pursues an egalitarian society to replace the current one.

Of course, coalescing around a set of political objectives is just one of the corrections demanded of the movement. The other correction is one of tactics and this is less clearly a matter of consensus. This past January a popular revolt in a working class neighborhood of Burgos, Spain challenged excessive ideological attachments to pacifism. The neighborhood of Gamonal had for months petitioned and marched against plans by the mayor for a boulevard and parking lot in their neighborhood, spending millions of euros on the project while thousands there are without jobs and while social services are shuttered. Their protests ignored, in January residents took the direct action of blocking work on the boulevard which escalated into days of pitched battles between riot police and protesters.

The revolt in Gamonal was marked by widespread community solidarity. Arrests each night provoked hundreds to descend on police stations to demand their release. During skirmishes with police, protesters were sheltered by residents, ending in police storming into buildings to make snatch arrests. In the end, the boulevard plan was suspended, but the protests continued, demanding the unconditional release of all those arrested. The idea of the Gamonal Effect was born out of this revolt; that defiant, popular revolt had won and could be replicated.

The lesson to be taken out of this isn’t even that mounting barricades or lobbing stones at riot police is the most effective method. The lesson is that government and political systems that we consider unrepresentative can’t be lobbied or have their behavior altered by massively attended protest marches. Instead, they must be confronted and defied with a diversity of tactics where no single tactic is romanticized. In terms of Saturday’s March for Dignity in Madrid, for me it’s not about persuading the government to accept their demands but of inspiring the masses out of their resignation. The 1,700 riot police being deployed in Madrid to contain the protest suggest authorities are afraid that their recovery hasn’t won social peace, but reignited the conflict.

The Troika and Portugal’s Democracy Can’t Coexist

That time of year has returned to Portugal, when inspectors from the IMF & European Union arrive in the capital, negotiate behind closed doors with the country’s leaders, then disappear so the finance minister and deputy prime minister can brief the Portuguese public a few days later about the new sacrifices that are meant to prevent the next round of sacrifices, the same dishonest narrative presented the last several years. For the 2014 budget the government seeks further privatizations, salary cuts between 3.5% & 12% for hundreds of thousands civil servants, 10% cut to public sector pensions, and an increase in the retirement age. These deep public sector cuts for 2014 combine with this year’s “enormous” tax increase that will continue in effect for the foreseeable future.

The outrage to the measures was swift. On Saturday, tens of thousands marched in Lisbon and Porto in demonstrations organized by the main trade union federation, CGTP. Next Saturday, Que Se Lixe a Troika (screw the Troika in English) will hold demos across the country in an effort to repeat the success of mass demonstrations it organized in the spring and last fall. CGTP has called for a demonstration at parliament on the 1st of November to demand the rejection of the austerity budget, and sectors across the economy are organizing rolling strike action, from the dockworkers to the postal service and later the entire public sector with a general strike on the 8th of November. It’s easy to fear that the opposition on the streets will once again fall short, contained by low ambitions of political parties and union leadership, as has happened in previous protests, allowing the government to ignore them and press on with its budget cuts and tax increases.

While the protests and the outrage on the streets can be ignored or dismissed, there has been one voice against the austerity that the government and the Troika live in complete fear of: the constitutional court. A number of Troika imposed austerity measures have met a swift death in the constitutional court. The court has twice ruled against measures taking away the Christmas & vacation benefits of civil servants and pensioners, it has struct down cuts to unemployment benefits & sick pay, and this past September it ruled against the government’s “mobility scheme”, a cynically named measure to ease layoffs in the public sector. Having successfully blackmailed several European democracies into complying with austerity programs over the past several years, the frustration of the Troika continues to mount as expectations are high that some of the more controversial austerity measures in the 2014 budget will face their demise before the court.

The Troika is already making its next move in Portugal. For the past few weeks, there’s been a steady application of political pressure on the judges of the constitutional court. European officials warned against “political activism” by the court. The president of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso warned of the need of all Portuguese institutions to have “responsibility” to ensure Portugal’s return the markets. In private, European officials are more frank, with one Portuguese newspaper quoting an official describing the political pressure as “live ammunition” that will continue until the judges get the message: approve the measures even if they’re unconstitutional. It’s not hard to see where this is all leading Portugal. Having “rescued” Portugal from defaulting on its national debt, the Troika is preparing to rescue the country from the constitution crafted in the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution that brought to an end decades of fascist rule.

The constitutional court isn’t the only threat to the Troika’s program. This latest austerity package follows the near collapse of the coalition government over the summer. Paulo Portas, the leader of CDS, the junior party in the coalition, had delivered an “irreversible” resignation over the government unshaken commitment to austerity despite its well documented failures. After two weeks of political turmoil and failed talks for a government of national salvation with the opposition socialist party, the “irreversible” resignation became reversible, Paulo Portas winning a promotion to deputy prime minister. The commitment to the austerity program, however, remained unaltered.

With that commitment, the country remains condemned to a vicious cycle of political crisis and the Troika reimposing austerity through blackmail and threats. The country slides into a neoliberal dystopia where the young either emigrate or are unemployed, and where the shrinking pensions of their grandparents must somehow provide for three generations. If asked to choose which is the impossible path to pursue, to defy the Troika and cease the self-inflicted wounds of successive austerity measures or to continue on indefinitely slashing the welfare state to divert more of Portugal’s wealth to paying a national debt that can’t be paid, I would argue the second option is the impossible path and there’s no alternative but to expel the Troika before every last conquest of the Carnation Revolution is lost.